For anybody interested in this site, my more recent writing can be found at my film review site 75 Words or Fewer – it’s a kind of film-diary of a wide range of films, some quite obscure. Hope to see you there!

Ben.

The Cinema of 1941

For anybody interested in this site, my more recent writing can be found at my film review site 75 Words or Fewer – it’s a kind of film-diary of a wide range of films, some quite obscure. Hope to see you there!

Ben.

Come Live With Me was the first of three films to star James Stewart in 1941. Along with Ziegfeld Girl and Pot O’ Gold these titles are little-viewed these days, perhaps only by Hollywood enthusiasts.

By looking at Come Live With Me I will outline a few ‘pleasures’ of watching classical Hollywood cinema.

Signs of the time

Much of the pleasure comes from aspects that are inherent in the film and outside of the filmmakers’ control. These would include aspects of form, such as the certain quality and texture of the black and white of 1940s film and the square framing within the 1.33:1 aspect ratio. Others aspects are embedded within the world of the film itself: the costumes, the behavior, the language, the performance styles, the voices, the locations, and the setting, all of which are of course infused with a sense of the period in which the film was made.

Titles

The title sequence is exciting enough. A logo, in this case a lion roaring within a celluloid ribbon frame, recalls other experiences at the movies – MGM’s The Wizard of Oz, The Mortal Storm, The Thin Man – and promises just as much. It’s both a promise of things to come and a stamp of proof that you’re at the movies.

Then the title sequence itself. In this case over comic illustrations of its stars; lighthearted, fun, throwaway, and indeed unusual for a movie of this period. Then in giant letters the headliners:

Here we have a typeface that appears indicative of the 1940s: sleek, smooth and modern. While absolutely standard at the time, such details can bring pleasure to a viewer who notice it as a sign of the period .

These names promise a lot. Again they recall your previous experiences with them and open a kind of contract that they will perform as they have before, fulfilling your expectation and desire to see them as you know them.

As the titles continue, scanning each one for recognisable names is a quick and silent game that moviegoers play.

Perhaps they recognise composer, supporting actors, or screenwriter (In this case the W.C. Fieldsian names of Patterson McNutt, based on a story by Virginia Van Upp). Of course the big one is director. Perhaps it’s going to be a Raoul Walsh, an Ernst Lubitsch or a Michael Curtiz movie – two of these not that likely in a lighthearted comedy as this. In this case the director is Clarence Brown, a director most famous for his silent classic Flesh and the Devil (1926).

Stars

The movie begins with a subplot about a socialite couple, Bart and Diana Kendrick. At the beginning of the evening they leave the house together like a refined husband and wife but when they get to the street they hop into separate taxis. Her boyfriend joins her for the ride while Bart heads to the hotel of his mistress, Johnny Jones, played by Hedy Lamarr, the star of the movie.

Nothing halts the flow of a Hollywood movie like the entrance of its female star. She is in the next room when Bart enters and sets down a gift on the table – a mechanical musical dancing ballerina. When Hedy Lamarr enters the camera pans from the dancing object, up her body and to a close-up of her face, which takes over the frame. She has been complexly lit, her hair backlit with a halo around its edges, her pupils, lips and earring glinting, and a strip of light that draws itself across her eyes. This kind of attention in the composition of the female star is very common in classical Hollywood cinema and creates a heavily stylised image. It serves to create an aura around the woman, a revery that works to construct the image of the female star as glamorous, ethereal, and ideal. Of course there is great pleasure to be had from the mere look of the star, partly a marveling at the combination of clothes, hair, make-up, body and face, as well as an idealised reflection of the human image. In this case the exoticness of the character is heightened by Hedy Lamarr’s trademark accent, adding a touch of European sophistication which serves to remove her from the commonplace even further.

The Set-Up

Many a Hollywood film has gone to lengths to justify its narrative concept through a precarious set-up, and often demands a generous suspension of disbelief. In this case Johnny knows that she is staying in America illegally but imagines that she can spend the rest of her life with Bart. During this very scene an immigration official (conveniently) appears – played by the prolific character actor Barton MacLane – and explains how she must leave the country immediately. In an aside with the immigration official Bart explains how if she were to return to her home country she would be ‘liquidated’ like her father. Although not explicitly stated, Bart is referring to the troubles of war-torn Europe and her homeland of Austria. The official actually takes pity on her, and because of the way she took the news of her deportation so bravely, he returns to the room to see her. Here the official gives his reason for admiring her and comes up with a solution to her problem:

Admittedly this is highly unlikely, but there is pleasure to be had from the silliness of this set-up. It is clearly only there so that the character can now attend to the comic business of being forced to marry a stranger. It is also quite rare that the character who appears to be the antagonist ends up offering a solution to the protagonist’s problem.

The Apartment Scene

James Stewart plays Bill Smith, a hard-nosed down-and-out penniless writer. We find him on a street bench about to pick up a cigarette butt off the pavement when Johnny steps on it accidentally. He’s annoyed but she continues on. Later that night they meet at a cafe while taking shelter from the rain. Accusing the waiter of stealing his money, they both end up kicked out and in a cab together. They soon discover that their names are ‘Smith’ and ‘Jones’ – ‘an evening of coincidences’ Bill calls it. The cab driver cynically thinks of them as pseudonyms as cover for a shady liaison. When she discovers that he lives alone and is truly penniless, she thinks her luck is in, that she’s discovered a candidate for her whirlwind marriage. He’s of course surprised when she invites herself over.

Back at his apartment here is what follows:

Here the pleasure comes from the concise dramatic set-up of each character understanding the situation differently. Bill thinks she’s over for a liaison but what she really wants is to propose. It is particularly engaging for the audience because they are let in on their contradictory motivations before the characters themselves have figured it out.

The scene is also a very funny one. His pennilessness is almost Chaplin-esque. Chaplin’s little tramp would often transform his poor surrounding into an illusion of luxury (a teapot would act as a baby’s bottle, a cigarette case of butts would become a grand selection of fine choices). Just before this scene Bill talks of his great library of books (which you only have to go down to the pawnshop to read). Here he talks of a nice open fire, pine logs, curling flames and a faithful dog. Offering Johnny a drink he suggests a ‘nice warm beer’ as though it were a fine wine. Declining, he instead confidently offers her a cigarette only to find the case empty.

Indeed this scene is styled like a comedy scene. Chaplin’s cinema often framed its characters squarely ahead and left them to their comedy business, making sure that their entire body was within the frame. Similarly the Marx Brothers were often left within a static frame and allowed to perform out their routines in full (see the card-playing scene in Animal Crackers). Here the scene is filmed front-on and in a single take, which allows the actors time to play out awkward pauses and also, in James Stewart’s case, to make use of the space around him.

Then comes the great line. Almost giving up, Bill says, ‘Well, I guess that takes care of the formalities’, sits on her arm rest and plants a kiss on her face. In return he gets a slap. When she asks him, ‘What do you mean by doing a thing like that?’, Stewart’s expression comically encapsulates confusion and irritation.

He soon gets the chance to perform a big comic double-take when he asks her:

Bill: Well what did you come up here for anyway?

Johnny: I came here to ask you to marry me.

Stewart’s performances were often laced with comedy, but he was subtle about being funny and controlled it well. Here his comedy isn’t obvious – he keeps a stern demeanor throughout the scene – but he busies himself with comedy business, moving around the room in a single take.

In Bed Apart

Needless to say Bill eventually accepts the proposal and soon enough they both find that they are actually falling in love with each other, even though Johnny won’t fully admit it to herself. Even so Johnny rejects Bart’s proposal and Bill’s writing sessions become obsessed with her. Bill soon decides to take Johnny on a honeymoon, even though she is still not entirely sure is she loves Bill.

They eventually end up at his grandma’s place. Like many grandmothers in Hollywood movies she is impossibly wise (see An Affair to Remember (1957), for instance), so much so that she makes decorative plaques brandishing proverbs such as, ‘What Fools These Mortals Be’ and ‘Time Heals All Wounds’. This philosophizing rubs off on Johnny and she soon comes to fully appreciate Bill.

At the climax of the film Bill makes excuses to visit Johnny’s room, giving her a flash light in case she has to signal for his assistance. They soon find each other in separate beds, but it turns out that the wall between them does not fully reach the ceiling. As we see here this leads to the possibility of an interesting composition and dramatic set-up. But first in the scene comes an exquisite little moment:

Bill has been trying for so long to win her affections and when he has almost given up he lights a cigarette which illuminates the proverb on the wall. What is sublime about that moment is that he does not look at it. Many films would have had its character look right at it, acknowledge it, and continue on with renewed confidence. In this case it is subtle, funny and poignant.

Lying in bed their emotional separation is neatly represented by the wall between them. It also serves to make the poetry reading more poignant by the fact that they cannot see each other, that Bill cannot see the moving effect it is having on Johnny.

Popular cinema can be very perceptive of human traits and life situations. Its talent is in representing these common situations in a stripped down, concise form that is both far neater than tangled real-life situations, but also far more stylised. This moment here is a romantic one that appeals to the common experiences and desires of its audience, and here part of the pleasure comes from the distillation of a complex situation into a clearly defined dramatic concept: he is in love with her and she is falling in love with him.

The Climax

Briefly complicating the drama before its conclusion is the arrival of her married boyfriend Bart who comes to profess his love to Johnny. This angers Bill who leaves them together. Back alone in his room he sees the car leave the driveway and believes that Johnny has left him for Bart. The following scene then plays out:

Within here is the moment of Bill’s revelation that she has not left him, neatly conveyed by the flashing of the torch he gave her in case she needed him in the night. The incomplete wall then becomes an object that can be penetrated; Johnny appears in the space, again exquisitely framed, and Bill steps up for their first passionate kiss. Strangely, they now look into the camera as though the viewer were an intruder on their situation. Do they remain Bill and Johnny at this point or do they become James Stewart and Hedy Lamarr?

Why this happens at this stage I do not know, but it’s almost as if the viewer becomes accepted into the film in the most extreme way possible, by actually affecting, and interacting with, the characters. It is also pleasurable in its surrealism, a comic moment that seems to have little justification.

So here is a movie almost plucked at random from 1941. It was difficult enough to get hold of and indeed my copy is a bootleg. The film is certainly not revered as a classic but even as an example of standard Hollywood output it contains many of the factors that makes classical Hollywood cinema pleasurable more widely.

Christian Hayes.

Throughout the 1930s, America, alongside much of the rest of the world, struggled through the Great Depression. While much of Hollywood cinema appeared oblivious to the Depression, there was also a strong current of films that attempted to engage with economic and social injustice, including social realist films such as Our Daily Bread (1934), Black Fury (1935), and The Grapes of Wrath (1940); prison films like 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932), I Am A Fugitive From a Chain Gang (1932) and You Only Live Once (1937); gangster films such as Little Caesar (1931), Angels With Dirty Faces (1938) and The Roaring Twenties (1939); as well as musicals, particularly the Busby Berkeley Gold Diggers series. Some of these films explicitly endorsed the new president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, begun in 1933, a social program aimed at tackling poverty. In the 1930s director Frank Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin brought us, alongside other films, two of the most quintessential of the ‘New Deal’ films, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939.) In 1941 Meet John Doe followed, starring Gary Cooper as Long John Willoughby and Barbara Stanwyck as newspaper journalist Ann Mitchell, who puts ‘common man’ Willoughby in the public eye, under the name of John Doe, as a representative of ‘the people.’

This theme of the possibility of a symbiosis between a ‘common man’ and ‘the people’ was key to the ideology of Capra/Riskin’s 1930s ‘New Deal’ films. For example, in Mr Deeds Goes To Town a ‘common man’ inherits millions from a long lost relative but decides to give it all away to ‘the people’ in the form of aid to farmers dispossessed by the Great Depression, allowing them to buy the land back at whatever rate they can, with the money they make from farming. This appears to be an endorsement of the emphasis on aid to farmers within the Agricultural Adjustment Administration of Roosevelt’s New Deal, although admittedly asking for more than was being offered at the time. It particularly parallels with the Resettlement Administration instigated in April 1935, which resettled struggling farmers into communities in more productive areas and gave them low-interest loans to help pay for production expenses and basic living.

In Mr Smith Goes To Washington scheming businessman Jim Taylor (Edward Arnold) takes advantage of the popular intermeshing of the concepts of the ‘common man’ and ‘the people.’ Taylor manipulates naïve Scout Leader Jefferson Smith (James Stewart) into running for congress, aware that he will win votes but be likely to need ‘help’ with the use of the power given to him. Smith trumps Taylor, however, taking land Taylor intended to acquire for business purposes, to use instead in setting up a camp that would allow holidays for young Scouts. As ‘common man’ Smith succeeds in setting up this camp intended to inspire the young, who Smith specifically emphasises are ‘the people’ of tomorrow, the film nevertheless maintains the over-simplistic intermeshing of these two concepts.

By 1941 there were some that felt that the social agenda in Hollywood cinema was ripe for parody, critique and analytical scrutiny. Likewise some felt that Roosevelt’s New Deal had not been effective enough in its attempt to solve the country’s ills and that this movement deserved some criticism. In Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941) we see an example of this parodic, critical sensibility as popular film director John L. Sullivan decides he wants to make a serious, social realist film and sets out on the road in search of ‘the people.’ Sullivan ends up on the chain gang and discovers that these ordinary people in fact want to see comic cartoons and so decides that his film should likewise be a comedy. Here Sturges implies that a large proportion of the social realist films of the 30s had failed, since they did not take into the wishes of ‘the people’ that they claim to be representing. Another example of this detachment from the social agenda can be seen in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) in which Kane uses the words of social progressivism merely in order to trick the people into voting for him.

In both Mr Smith Goes To Washington and Meet John Doe ‘the people’ are tricked into turning against our hero, the ‘common man’ who represents them, by being told that he is crooked. A crucial difference between the two films, however, is that Meet John Doe adds to the mixture an extended challenge on the notion that one individual can ever represent the ‘common man’ and also strongly undermines the popular intermeshing of the concepts of the ‘common man’ and ‘the people.’ Meet John Doe is hardly, however, an outright critique of the social agenda and the New Deal. Instead these areas are to some extent bypassed in favour of a complex debate on the subject of the mass media and of its manner of simplifying and unifying debates. The film shows in detail the way that the mass media has at once both enhanced the possibility for a ‘common man’ to speak for ‘the people’ in a positive way, since it can spread an individual’s messages out towards the populace, and destroyed this possibility, since the media ultimately becomes exploited by the wealthy for their own ends.

As we shall see this emphasis on the dangers of the mass media is greatly enhanced by the fact that ambiguity is raised to the level of being a central theme and style. I will suggest here that the ideological standpoint of Capra and Riskin’s ‘New Deal’ films are upset in Meet John Doe, which may be in part the result of a rising distrust of the social agenda in Hollywood. I focus, however, on the rise of Fascism in Germany and America and the ways in which this has also impacted upon the film’s representation of social issues. Ultimately it is proposed that neither Nazism nor the social agenda is the film’s central theme, which appears rather to be a fascinating and complex modernist challenge to simplistic ways of seeing the world. It should also be noted that Meet John Doe was the first (and only) film that Capra and Riskin fully-funded with their joint production company Frank Capra Productions, after leaving Columbia Pictures. As such, while the more radical elements of the film can certainly be related to their socio-historical context they can also be considered to point to previous restrictions upon the filmmakers’ artistry by the conventional Hollywood style.

————

In Meet John Doe young journalist Ann Mitchell (Barbara Stanwyck) is about to be fired from her job at ‘The Bulletin’, recently re-named ‘The New Bulletin’, for being old-fashioned and determines to get her job back by putting out a final column that will give the editor the “fireworks” that he wants.

Mitchell’s column carries a letter that she has made up, in which a man states that he intends to jump from the Town Hall at midnight on Christmas Eve in protest against the “slimy politics” that he feels have kept him unemployed for four years. The letter has the town up in arms and Mitchell gets her job back by suggesting that the newspaper choose one man out of the hundreds that have turned up at their office in search of work to pretend to have written the letter and be the face for a series of articles in which Doe protests against social injustice.

From the outset then arguments made in earlier Capra/Riskin films against crooked politics and in favour of a true figurehead for ‘the people’ are problematised, as we are made aware of the often-dubious motives behind the representation of these issues within society. In this case, Mitchell and her editor’s primary motives are economic, not moral, since she wants her job back and he wants to boost the paper’s circulation. As the story progresses Doe, aided by the investment of businessman D. B. Norton who also owns the newspaper, becomes a national icon, with John Doe clubs being set up throughout the United States. Norton, however, intends to use Doe’s success as a means of tricking the public into voting him into the White House, by giving Doe a script for a speech that endorses a “third party”, suggestive of the Nazis’ ‘Third Reich’, to be led by Norton.

The film is particularly interesting in the way that it shows the filmmakers’ attempt to intertwine their continued interest in the subject of the New Deal and social inequity with a subject not obviously related to it, the growth of the Nazi Party in Germany and Nazi-affiliated organisations in America. Although not referred to directly the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, which had instigated the Second World War, is key to the way in which these subjects intertwine.

As Saverio Giovacchini has impressively illustrated in Hollywood Modernism – Film and Politics in the Age of the New Deal (2001) the Nazi-Soviet Pact had a strong impact on the Hollywood community. For example, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League was broken apart due to the differences between the large proportion of hard-line Communists, who continued to back Russia, and those unwilling to accept Russia’s partnership with Germany. The HANL was an effective organisation with, as the FBI noted in the 1940s, a “membership at the peak of its influence [of] approximately four thousand” and whose “influence spread to many times that number” (83.) [1] It is even tempting to see in the manipulation and downfall of the socially-progressive John Doe Clubs by the Fascist businessman D. B. Norton a direct allegory of the destruction of the biggest Hollywood ‘Club’, the HANL. It can be argued that the influence of the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the destruction of the HANL has impacted upon the film, making it more complex. The filmmakers find themselves no longer able to maintain the naïve ideological support of the left displayed in previous ‘New Deal’ films, since the left is now tainted by its association with Nazism.

The self-destruction of the HANL may also have seemed to some to be a sign marking the Hollywood community as weak. The film’s title Meet John Doe is suggestive of another of Hollywood’s failures as well as further reason for the filmmakers to be cautious about speaking in support of social reform. The title can be considered a direct reference to and challenge of the claim made in the title of the Hollywood Theatre Alliance’s extremely critically and commercially successful 1939 production Meet the People. Giovacchini notes that the title of this “autobiography of the Hollywood community”, Meet the People, summarises well this production’s “attempt to obviate one of its glaring shortcomings”. He comments that the play reversed theatre’s “normal East-West trajectory and travel[led] to Broadway from Los Angeles” and that “For many 1930s intellectuals, a thriving theatre was evidence of a thriving intellectual life” (109.) Meet John Doe, however, puts the brakes on this hope that the Hollywood community might speak for ‘the people.’ The film, for example, slyly critiques Hollywood casting-practices as journalist Ann, casting for the role of ‘John Doe’ sees a number of characters played by unknown actors, but nevertheless picks John Willoughby, played by Gary Cooper. A similar point is being made here as in Sullivan’s Travels when the film director trying to escape Hollywood for the ‘real world’ continually finds himself returning to Hollywood against his own will. The implication in both cases is that there is something innate in Hollywood itself that makes it unable to relate with the real world and instead capable only of narcissistic self-reflexivity.

This challenge upon the Hollywood community’s abilities in effecting a symbiosis of the ‘common man’ and ‘the people’ is about more than the HANL, however, and rather can be considered as part of an extended challenge upon the mass media. Admittedly one element of the narrative of Meet John Doe suggests that the John Doe Clubs can exist beyond politics – emphasised particularly in Capra’s heavily Christianised conclusion. Nevertheless the overwhelming feeling of Meet John Doe is of a fallen world in which Roosevelt’s ‘Fireside Chat’ radio broadcasts and Hitler’s Nuremburg Rallies co-exist as media forces allowing those with wealth to attain power (both of these are parodied as means by which the John Doe Club grows in strength, allowing Norton power.)

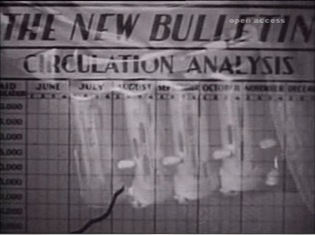

This challenging of Hollywood cinema as one aspect of the mass media even extends to an undercutting of the formal techniques of the Classical Hollywood style. This can be seen, for example, as a montage of the popularity of Doe’s “I Protest” column in the New Bulletin culminates in graphs showing boosts to the newspaper’s circulation. Likewise a montage showing the growth of the John Doe clubs is preceded and discoloured by Norton’s assertion that this is what he wants in order to take power.

Ordinarily in Hollywood cinema a montage sequence is perhaps the least ambiguous element of the whole film, serving simply to convey progression through time by re-asserting a single point, perhaps a hero’s accumulation of success or various examples of a romantic couple falling in love. These montage sequences in Meet John Doe, however, clearly have a double-meaning and so imply a co-existence of good and evil, since the viewer is forced to recognise that he is at once glad that the John Doe idea is a success, since it brings happiness to many, yet anxious that it is being used for immoral purposes. The film as a whole can be said to have an overall style of ambiguity. As well as there being at times a multiplicity of meaning, at other times a cause can also have a multiplicity of effects. This can be seen, for example, in the contrasting reactions that the letter Mitchell publishes in The New Bulletin has on the Mayor, the Minister, Norton, an aristocratic woman, the general public and the poor of the city.

Meet John Doe was reported at the time, in what appears to be a promotional article from the film’s distributors Warner Bros. Pictures, to have used “over four thousand extras” [2] (the film’s trailer claims five thousand) [3.] The same review also comments, which seems just about possible, that the film has 137 speaking roles. The filmmakers’ aims then seem to be equally ambiguous: while the former statistic suggests that Capra and Riskin are earnest in their wish to speak for the masses of people living in poverty, the latter emphasises excessively the multiplicity of voices that compete with one another over this subject matter. This ambiguity in the film can be gauged in the reviewer’s somewhat confused language as he perceives the film to have “drawn attention to the human problem of the average man.” The film’s style of ambiguity follows in part from its theme of the complex, intertwining and inseparable nature of the relationship between the representation of a thing and the thing itself; in the film’s narrative John Doe represents the former and Long John Willoughby the latter.

Indeed this theme of ambiguity comes to a head as John recounts his dream to Mitchell, in which he sees himself as at once both himself (although he has actually taken to calling himself John Doe) and Mitchell’s father (who wrote the original material Mitchell uses for the Doe speeches.) In John’s fantasy he takes advantage of the ambiguity inherent in his unique situation of having a double-identity, watching Mitchell as she intends to marry another man and at the same time severely punishing her, in the role of her father, by smacking her. Far from being simply a comical aside this dream presents, as much as Hollywood will allow, the distortions to the human character that can happen when a person is given excessive amounts of power.

Rather than fantasize about marrying Mitchell himself John instead takes a perverse pleasure in his dual position of being able at once to dole out ‘justice’ to her while at the same time being able to claim a lack of responsibility, as a mere onlooker. This strange split mind is the result of his taking on the role of John Doe, the moral arbiter of ‘the people.’ John’s apparent inability or lack of will to intervene while watching as ‘John Doe’ in this dream is further a reflection on the cinematic viewer who hides himself away in a darkened room while watching films, allowing himself anonymity while playing out his own fantasies on the big screen. In this dream we can then also see that it is not simply the mass media that destroys the possibility of a positive symbiosis between the ‘common man’ and ‘the people’, but also something inherent in human nature.

In Freudian terms we can say that John Doe has become for ‘the people’ a ‘collective superego.’ The superego in an individual is the unconscious aspect that is to an extent detached from the ego (the ‘I’) and enforces regulations by which the ego must abide. As Mark Edmundson succinctly summarises in reference to Adolf Hitler, but which can also be considered representative of John Doe’s situation in the film:

What he offers to individuals is a new, psychological dispensation. Where the individual superego is inconsistent and often inaccessible because it is unconscious, the collective superego, the leader, is clear and absolute in his values. By promulgating one code — one fundamental way of being — he wipes away the differences between different people, with different codes and different values, which are a source of anxiety to the psyche. [4]

In his dream John finds psychological dispensation in the figure of Mitchell’s father, whose words, seeming to have come to speak for the people, serve as a ‘collective superego’ for him. For the populace the image of John Doe takes on the same ‘collective superego’ role that the father has for John, since they follow what Doe is telling them in a somewhat naïve fashion. In each case the ambiguity that exists as a result of the appearances of similarity between the real and its representation is presented as potentially dangerous.

This more sinister aspect of John’s character should not be overstated since the end of the film also directly links him with Christ who we are told was the first John Doe “2000 years ago.” Doe can thus equally be seen as a ‘good’ version of the subsuming of power to a collective superego (i.e. God) in contrast to the ‘bad’one (of the fascist D.B. Norton.) Nevertheless, the manner in which the film engages with class issues can be seen, in terms of the narrative structure, to undercut our identification with the character of Doe as much as Norton. For example, Norton owns a large mansion and we see him at one point on horseback in the grounds of the mansion, watching an intricate motorbike display put on for his purpose appearing as an aristocrat in control of the modern world. Later we see him with a map of the United States covered with pins showing where he has managed to have John Doe Clubs set up, seemingly controlling not only the political figureheads of the city that are in the room, but the nation itself.

We can see here the central aspect of the film’s argument on class issues, which is that society is continually endangered by the possibility of a misbalance of power whereby one individual comes to represent ‘the people.’ But this individual could just as easily be ‘common man’ Doe as Norton. Meet John Doe is for this reason fundamentally different from, and arguably darker and more complex than, Capra and Riskin’s earlier ‘New Deal’ films, since it does not allow us a properly believable positive resolution to the class issues that it raises.

In its paralleling of its two key themes – class difference and the threat of Nazism – Meet John Doe presents each in a manner that is quite different to the way they appear in other films of the time. The model of absolute dictatorship in Nazi Germany comes to call into question the naivety of the hope in previous Capra/Riskin films for a ‘common man’ to emerge that would serve as the figurehead of ‘the people.’ Likewise the theme of Nazism is presented throughout the film as related to capitalism and the dangers of the modern world, since the businessman D. B. Norton’s motives seem to be at once for both money and absolute power and he uses the media for this effect. In spite of the fact that the film has to carry these two only partially-linked themes, however, the whole thing hangs together dramatically very well. This is perhaps because neither of these more obvious ‘issues’ dominates the film and another key theme – that of a modernist reaction against unified manners of thinking, of seeing the world and of acting within it – draws these together. Meet John Doe‘s theme and consequent style of ambiguity bring up questions about the ways in which one idea or action can have multiple, often contradictory, meanings and about the way that differences are often unnecessarily and dangerously elided. As a result Meet John Doe draws together the key ‘issues’ of the time, putting them within a critical context all too rarely seen in Hollywood cinema.

Ben Dooley.

[1] Saverio Giovacchini, Hollywood Modernism: Film and Politics in the Age of the New Deal (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001.)

[2] Unnamed author, ‘West End News – New and Exciting Film Experience!’, Warnergram, 26 September 1941, available at the BFI Library.

[3] The trailer can be found at: http://www.tcm.com/video/videoPlayer/?cid=14267&titleId=3827

[4] Mark Edmundson, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/30/magazine/30wwln_lede.html, 30 April 2006.

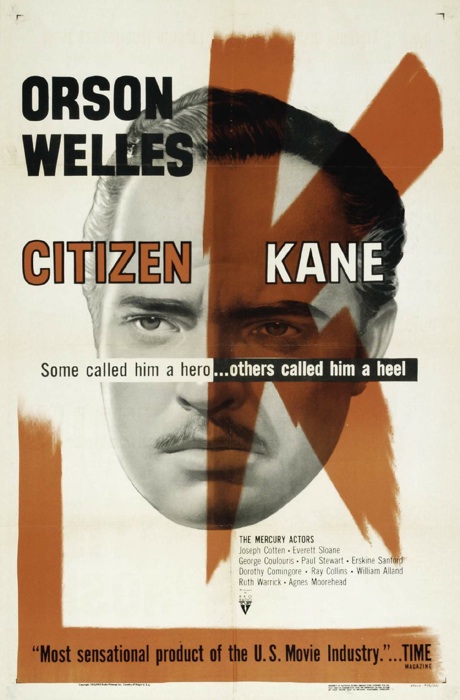

For a mere $1,200,000 you could own an Academy Award from 1941. On Tuesday 11th December 2007 Sotheby’s New York will be auctioning none other than Orson Welles’s Best Screenplay statuette for Citizen Kane, the only Oscar he ever received. One of the most iconic pieces of memorabilia ever to come to auction, it is now conversely famous for not being a Best Picture or Best Director Oscar, often regarded as a tragic ‘mistake’ by the Academy and as one of many injustices in Welles’ career.

Of course it is not a mistake at all for the Academy to make such decisions. The Oscars are often criticised for choosing a ‘lesser’ film over a ‘greater’ one – Ordinary People (1980) instead of Raging Bull (1980) is often rolled out as an example – but any movie fan would be supremely naive to believe that they are judging the Best Picture category using the same criteria as the Academy. Movie fans are often solely referring to aesthetics: form, performance, narrative, style, whereas Academy decisions are often determined by political or financial factors, leading to the Academy’s voting to reveal a set of brand values. Films that appear to push boundaries, such as Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) or Crash (2004), are ultimately bound by a set of aesthetics that constrain the scope of the writing and visual style, which in turn constrains the social comment.

Best Picture awards for expensive epics that appear to be rewarding aesthetics are more likely recognising financial gain (Gone With the Wind (1939), Ben-Hur (1959), Titanic (1997), The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)). Off-screen Citizen Kane had already caused highly publicised difficulties with the powerful William Randolph Hearst, and on-screen it was an audacious, young movie with a fresh visual style that revealed a rebellious spirit. The Academy values are not always easily visible, leading filmgoers to resent the lack of Best Picture Oscars for films such as Citizen Kane or Raging Bull.

The Best Screenplay statuette has also become an icon of a long-standing authorship debate. Many have questioned Welles’ contribution to the screenplay of Citizen Kane, which was also written by veteran screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz. Debate has raged over exactly what each writer brought to the screenplay, some believing that Welles, being the auteur that he is, of course co-wrote the screenplay. American critic Pauline Kael famously criticised Welles in her essay ‘Raising Kane’ (1971) for his lack of involvement, championing Mankiewicz as the neglected author (indeed he penned the entire first draft).

If you want to get your hands on clues as to Welles’ contribution to the script, his copy too is going under the hammer at the very same auction. Fully annotated and scribbled on, it’s another absolutely unique piece of memorabilia. Both items can be snapped up for a mere couple of million dollars. Go for it.

Christian Hayes.

Swamp Water is a very American movie. With its ‘authentic’ American dialogue, archetypal American characters, and its assorted Americana (the costumes, the accents, the barn dance, the music), Swamp Water is deeply grounded in American culture. It is therefore surprising that the film was directed by Jean Renoir.

Renoir defined French cinema in the 1930s with a string of classic films such as Boudu Saved From Drowning (1932), La Grande Illusion (1937) and La Règle de Jeu (1939). These films delicately balanced drama and comedy, often articulating serious themes with a light touch. Like many European directors before and since, Renoir left for Hollywood in an attempt to repeat his successes there.

A director’s move to Hollywood is often tied to the question of artistic compromise: can the filmmaker maintain their unique aesthetics and outlook within the rigid constraints of the studio system? Inquisitive viewers no-doubt search for stylistic trends that made it across the Atlantic. In the case of Swamp Water, apart from a few instances of an effortlessly gliding camera, they would find it difficult to link it to Renoir’s earlier films. But perhaps making any obvious connections is a red herring; it is perhaps most commendable for its authenticity and pleasures as a Hollywood film.

European Émigrés in Hollywood

Hollywood has a long history of hiring European filmmakers to work on Hollywood productions, be it directors, stars or technicians. This tradition goes as far back as the 1920s when directors such as Victor Sjöstrom, Mauritz Stiller, Ernst Lubitsch and F. W. Murnau moved to Hollywood in an attempt to apply their native success overseas. Some of these émigrés successfully transplanted their talents to Hollywood, as in the case of Sjöström’s The Wind or Murnau’s Sunrise, yet others like Stiller failed to make it very far in Hollywood. Ernst Lubitsch was the only one of these examples to maintain a long career in Hollywood (indeed both Stiller and Murnau died young).

Renoir’s film contrasts sharply to those being made by his fellow émigrés at the time. Ernst Lubitsch had recently made Angel (1937), Ninotchka (1939) and A Shop Around the Corner (1940), comic films set in European locales and with European characters and performers, including émigrés Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo (arguably the most successful of them all).

Similarly Billy Wilder had written Lubitsch’s Ninotchka and in 1941 was screenwriter of the screwball comedy Ball of Fire. He would go on to direct both Lubitsch-style comedies such as The Major and the Minor (1942) and more serious dramas, such as Five Graves to Cairo (1942) which included a pan-European cast of wartime characters, including Erich von Stroheim as Field Marshal Rommel. ‘Exotic’ Europe was often a defining quality of these films and indeed Hollywood was keen to exploit the ‘sophisticated’ sensibilities that these European filmmakers could bring to their films.

Other émigrés such as Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang continued to focus on the kinds of genre pictures that they had been making during the 1930s. In the case of Hitchcock there was still a clear British connection with an adaptation of Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1940) and the international espionage of Foreign Correspondent (1940). Similarly Lang continued making crime pictures in Hollywood, a genre he had really made his mark on back in Germany. Yet after films such as Fury (1936) and You Only Live Once (1937), Lang was soon making Westerns (The Return of Frank James (1940) and Western Union (1941)), the most American of genres.

Heading West

Indeed with its small-town milieu, good guys, bad seeds and corrupt Sheriff, Swamp Water closely resembles a Western. There is indeed a connection to John Ford’s regular contributors, through both Dudley Nichols the screenwriter and cast members such as Walter Brennan and Ward Bond. The theme of bringing law, morality and justice to uncivilized corners of America was a theme that ran through films such as Young Mr Lincoln (1939) and My Darling Clementine (1946), but has also been a key theme of Westerns more widely.

In many ways Swamp Water, Renoir’s first film in Hollywood, proves that he assimilated to Hollywood material much faster than his contemporaries. Indeed the film contains little sign of any European connection. From its very opening, with a rendition of the American hymn and jazz staple ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’ over the titles and a scrolling title card that pinpoints the action to Okeefenokee Swamp in Georgia, the film firmly enforces its American roots.

The film centres around a mysterious local swamp that breeds fear in the locals. Suspicion only grows when the bodies of missing hunters are discovered there and the locals wonder what kind of monster may be lurking in its darkness.

Indeed hiding there is the haggard Tom Keefer (Walter Brenann), a long-lost fugitive accused of murder. Cut off from civilization he has learned to survive amidst the alligators and deadly snakes that crawl around him. When Ben Ragan (Dana Andrews) finds himself in the swamp he is at first attacked by Keefer, but soon befriends him, believing in his innocence.

I would like to focus on two particularly striking moments in the film, both towards the end. The first occurs when the brothers Dorson track Ben and Keefer down to the swamp, intent on killing them. Keefer immediately suspects that Ben had led the brothers here to kill him: ‘You set ‘em on me. I should’ve cut your throat the first time you came at me, like I wanted to.’ In a test of loyalty, Keefer orders him to stand up and show himself. ‘They ain’t gonna shoot at you. Because you’re in cahoots with ‘em. Now go on, show yourself.’ Ben replies, ‘All right, Tom. If that’s what you think, I’ll show you.’

Ben stands cautiously and walks out into the open.

There is a moment of silence before a shot rings out and chips off a piece of the tree next to him.

Keefer instantly realises his friend’s loyalty and hurries to help him.

The second moment is soon afterwards when Keefer and Ben are being chased by the Dorson brothers. Keefer sets up a trap that involves the brothers having to run through a deadly ‘bog hole’. Watching close by, Keefer and Ben witness Bud plunge into the boggy earth, immediately up to his shoulders. He yells out to his brother, ‘Tim, hurry! I’m sinking! Get me out of here!’ His brother desperately attempts to pull him out with his rifle, but it’s no use.

As Bud is sucked deeper into the mud his screams become more desperate, yelling out his brother’s name, ‘You ain’t pullin’, Tim! Oh Tim, darn it! Don’t let me die in this mud!’ His last words are the chilling repetition of his brother’s name, the camera on a tight close up of his face as it goes under.

These two moments distil the relationships between these characters in a disarmingly honest way. Keefer suddenly fulfils his fierce desire: ‘I’m trying to find out if there’s anyone in the world that can speak the honest truth’, answering spiritual questions he posed to Ben earlier in the film about his place in the universe. Bud’s descent into the bog immediately conveys the love that had existed between these two tough brothers but also expresses the devastating disappointment of Tim in Bud’s voice, his child-like fear invisibly conjuring up an imagined past of Tim and Bud as young boys.

There are often viewers who have problems revering Hollywood cinema, siding with the perceived notion of European cinema, for example, as artistically ‘pure’ over a cinema motivated by commercial gain. Here are two brief examples of how Hollywood cinema can transcend the artificiality of the sets, the stylised performances and the commercial motivations of Hollywood as a whole.

Christian Hayes.

Jean Renoir arrived in America for the first time on New Year’s Eve 1940 on an American liner sailing from Lisbon to New York. He swiftly left the Big Apple for Sunset Boulevard and by the middle of January had been signed to a contract with 20th Century-Fox. It wasn’t until the end of May however, after having had a series of ideas for stories rejected, that Renoir was able to begin on his first American film Swamp Water, scripted by Dudley Nichols and based on a novel by Vereen Bell.

Despite having been relatively forgotten even in relation to Renoir’s American oeuvre Swamp Water, while at times frustrating, is ultimately impressive. It tells of the vast Okeefenokee swampland of Georgia and focuses on young Ben Ragan’s (Dana Andrews) encounter with Tom Keefer (Walter Brennan) an accused murderer who has been hiding out in the swamp for years. Particularly strong is the film’s use of depth photography in its location shooting of Okeefenokee as well as in some key dramatic scenes.

Likewise of interest is the film’s attempt to get at the accent of the American South, which, while possibly not in itself immensely researched, nonetheless feels accurate, with performances aided by the script’s strong sense of linguistic authenticity. The script also contains some sharp comic moments, a good example being Ben Ragan and Keefer’s daughter Julie’s (Anne Baxter) first romantic encounter, in which Ben tells Julie that “You’re a heap prettier than Mabel is, if you was a little bigger” to which Julie responds, “I could grow more maybe!”

In this piece I will focus, however, on the film’s central story, which on the surface might appear fairly melodramatic and apolitical and has indeed generally been received this way. Although Swamp Water was assigned to Renoir, rather than chosen by him, it nevertheless was of interest to the director who commented that, “it is still something to be able to direct a film with a story that is not completely idiotic.” Screenwriter Dudley Nichols was an established figure and had worked throughout his career with such directors as John Ford, Howard Hawks and Fritz Lang. Renoir and Nichols got along very well, no doubt not in small part due to the fact that Nichols’ previous experience with these directors must have left him very open to possible revisions of his work. I will argue here that while on the surface Swamp Water appears to be an escapist drama, it has a political subtext that touches at once on issues both of the American South and of the Europe that Renoir had recently escaped.

A key example of a theme in Nichols’ script that appears to have been worked on by Renoir is that of humans as being not dissimilar to animals. For example, Ben like his dog is an adventurer who gets easily lost, while Julie like her kittens is small but bites when threatened.

There is nothing in the film’s narrative or script, however, that could be seen to have prompted the decision to have Tom Keefer horizontally creep up on Ben the first time we see him, paralleling him with the alligators that haunt the swamplands; this seems likely to be Renoir’s image.

And the choice that Julie remain silent for a long-time into the film (which incidentally is perfect for Baxter’s acting, which is of a high-emotional tenor) and have wild hair and a wide-eyed performance, all seem to extend her appearance as a cat beyond those expressed on the page.

These images of Ben and Julie are undoubtedly fairly romantic and arguably mildly condescending towards the real people of small-towns in America. Indeed Renoir was close friends with Robert Flaherty, who arranged for Renoir’s journey to America; and Flaherty had made the famously condescending ethnographic documentary of the Inuits, Nanook of the North (1922.) And Renoir said of Georgia that it was “an old country, very primitive, with peasants who remind me of the inhabitants of very isolated corners of Brittany” and that “the families have no idea of quitting their wooden farmhouses. The tree which shades the porch has been planted by some ancestor.” (1)

On closer inspection, however, this theme is a little more complex than it first appears, since beneath the surface of this more romantic animal imagery there is also the image of the hunt. The brutality of rabbit hunting had been central to Renoir’s previous film La Regle du Jeu (1939), a symbol of human brutality: as a man is killed we are shown a close up of a rabbit being shot. In both films the hunt is presented as a social convention upholding bourgeois society’s cruel and arbitrary rules. In Swamp Water the culmination of Ben’s ostracism from his community is represented in his no longer being allowed to hunt foxes alongside his neighbours. But the villagers’ hunt can also be paralleled to their blood-thirsty desire to catch Tom Keefer and have him hanged.

In this respect Swamp Water can be considered a film about the lynch-mob mentality, following on from Fritz Lang’s fairly recent film for MGM on the subject, equally with an all-white cast, Fury (1936.) Seen this way Swamp Water’s opening image of a skull sitting on the top of a cross in the centre of the river which is a marker to help guide people through the river, can also be considered as suggesting that the film can be read as a Christian allegory of Jesus’ unjust crucifixion.

Considering the setting of Georgia it is strange that this film has no black characters (and very few black extras.) It is possibly the case that, just as with Lang’s film, it was thought that too overt reference to race could be dangerous. (2)

Despite this, however, Tom’s daughter Julie, while literally white, could certainly pass symbolically as black. Indeed her reputation in the village has been blackened by her father’s name and she is treated as inferior, forced to take on the role of live-in maid, one that in Hollywood cinema is traditionally taken by a black character. Equally when Ben takes her to a ball the community are surprised and while she receives some compliments the family for which she works disapprove, which is certainly suggestive of the racial issue of segregation.

A final image that suggests the racial allegory in the film is the quite blatant fact that despite Ben’s dog having the name Trouble he actually does not get Ben directly into trouble. This red herring is similar to the paralleling of Tom with the alligator, whose viciousness turns out not to be in Tom’s nature. In each case there is an overturning of our perceptions of a dangerous “other.” Key here, however, is the fact that these quite central and obvious negations of the danger of “otherness” do not seem to have any direct reference to racism against black people, but are far broader. Clearly this more general space for considering the unfair victimization of some form of “other” makes the film, like Lang’s Fury, equally open to being read as an allegory about the victimization of Jews under the Nazis throughout Europe.

While Swamp Water contains various hints that it is intended as in part racial allegory, most viewers today will probably not notice this and indeed neither would have many at the time of the film’s release. The initial script of Swamp Water was greatly cut by the time the film came together: a memo from Darryl F. Zanuck to Renoir pressing him to hurry the production along notes that the script, “has been cut to 137 pages. Over 45 pages have been removed”. (3) Equally, a key scene that Renoir shot was cut and Zanuck constructed another scene to replace the gap that had now been made in the plot. (4) It seems likely that a closer look at all the elements that didn’t make it into the film’s final cut, if available, along with the various discussions amongst the filmmakers involved in Swamp Water’s production might well yield further political aspects of the film. Nevertheless I would say that something of a political perspective remains in this film, if only in its overt argument against the victimization of an “other” that may well have been recognized by some viewers at the time, if on an unconscious rather than conscious level, as a reflection on the dangers of fascism.

Ben Dooley.

(1) Sesonske, Alexander, ‘Discovering America: Jean Renoir 1941’, Sight and Sound, Autumn 1981, pp. 256-261.

(2) Eisner, Lotte H., Fritz Lang, Da Capo, 1988, p. 164.

(3) Vitanza, Elizabeth, ‘Another Grand Illusion: Jean Renoir’s First Year in America’, The Film Journal, http://www.thefilmjournal.com/issue12/renoir.html

(4) Sesonske.

Citizen Kane holds the weight of cinema on its shoulders. Often cited as ‘The Greatest Film of All-Time’, the film maintains an unusual place in film history. This post attempts to outline one particular way in which the film gained its unique reputation.

The accolade in fact refers to the Sight & Sound poll taken every ten years. Kane took the top spot in 1962 and has not budged in over 40 years. In 1952 it was De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves that came out on top and at that point Kane did not even feature.

Although critics were enthusiastic about the film on its release in 1941, Kane was not a particular success with audiences. It had become partly-notorious for an attempt to suppress its release by William Randolph Hearst, the tycoon who took offense at the parallels between Kane’s life and his own. The film did however gain several major Oscar nominations alongside other key titles of the year such as How Green Was My Valley, The Little Foxes and The Maltese Falcon, claiming one win for Best Screenplay.

So something clearly changed between 1941 and 1962 for Kane to be selected as the pinnacle of all cinema. This shift can perhaps be pinpointed to post-war France where all the American films that had been prevented entry during the war suddenly flooded its screens. So its audiences were experiencing Hollywood cinema of the early 1940s in a condensed period of time, an experience that clearly had an effect on many of its young viewers. When the French magazines Cahiers du cinéma celebrated popular Hollywood cinema throughout the 1950s it was perceived as a strange affectation by other contemporary European film magazines such as Britain’s Sight & Sound.

However, when these very critics, such as Truffaut and Godard went on to spearhead the nouvelle vague in 1960, their films became praised as milestones in contemporary cinema. This therefore posed problems for Sight & Sound critics who were enamoured by the films of the nouvelle vague yet against the popular Hollywood cinema that the New Wave filmmakers celebrated.

‘The French Line’, a 1960 Sight & Sound article, took a look at the ten-best lists published by Cahiers du cinéma. They were pleased to find revered titles as Ivan the Terrible (1944), Les Quatres-Cents Coup (1959) and Wild Strawberries (1957), but were very surprised (and dismayed) to find titles such as Rio Bravo (1959), Run of the Arrow (1957), Wind Across the Everglades (1958) and Vertigo (1958). The author wrote, ‘One’s first reaction might be to conclude that these men must be very foolish’ [1] but based on the evidence of their films found it was hard for the writer to accept Resnais, Truffaut, Chabrol and Godard as fools.

Classical Hollywood cinema was therefore being reassessed in the 1960s and indeed many of our contemporary perceptions of cinema were cemented at that time. It was also a period during which the reputations of Hollywood figures were being reconstructed. For example Humphrey Bogart became a romantic cult hero for young movie fans – as reflected in Jean-Paul Belmondo’s adoration of Bogart in A Bout de Souffle – and retrospectives of Buster Keaton’s films elevated him out of the shadows as a master of cinema. Similarly Orson Welles became seen as a crucial cinematic icon.

One of the defining characteristics of Orson Welles’s cinema is a struggle for control. Indeed a great number of Welles’ films were taken out of his hands and re-edited (or chopped up), including The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Lady From Shanghai (1947), Othello (1952), Mr. Arkadin (1955) and Touch of Evil (1958). Then there were all those projects that never made it, either unfinished or doomed from the start, such as It’s All True (circa 1943), Don Quixote (circa 1955) and The Other Side of the Wind (circa 1972). [2]

In Welles’ persistence to make films in the face of resistance from studios and financiers he became an inspirational hero for filmmakers and cinephiles, his cinema ingrained with a message of never giving up for cinema’s cause.

Critics and cinephiles believed Welles to have been greatly misunderstood and mistreated by a Hollywood who could not see the brilliance in his work that was so clear to them. Welles’ tragic fall from grace and his role as an underdog against the system only heightened adoration for him. He became seen as a neglected ‘genius’ whose opportunity to flourish had been crushed by a system so clearly against originality. And it was Citizen Kane that defined this tragedy, becoming the iconic film that represented much more than the film itself.

The Sight & Sound poll reflects this shift and in 1962 we find the point at which Citizen Kane cemented an extraordinary reputation.

Christian Hayes.

[1] Richard Roud, ‘The French Line’, Sight and Sound, Autumn 1960 p.167.

[2] For more information on this see the illuminating documentary The Lost Films of Orson Welles (Germany/France/Sweden, dir: Vassili Silovic, 1995) which includes many clips from both unfinished films and curiosities.

Sitting with a friend in the bar at the Curzon Soho recently, after having watched a movie that we had both been underwhelmed by, I found myself bringing into the conversation another film, Citizen Kane, and the subject of a certain discomfort I have always had with this film. The argument went as follows: “While Welles evidently seems to feel that the story of Kane’s life is always from the point-of-view of one or other of the characters – never objective – whenever I finish watching the film I always feel as though I’ve been told a fairly substantial biographical narrative. And what’s more I can’t really remember and am not overly bothered which sections were told by whom and in what order… Because despite vague references to the storyteller within each of the flashbacks, the style of these flashbacks is nevertheless overwhelmingly omniscient.”

I wouldn’t of course retract the validity of either of the phenomenological cinematic experiences expressed above – nor necessarily the possibility that they may point towards weaknesses in the work. I can’t help but wonder, however, whether it was overly simplistic to imply that the central project of Welles’ film was to present an “anti-portrait”, a point blank refusal of objective identity, and with this a narrative about the complexity and mystery of the world.

Jorge Luis Borges took up this position on Citizen Kane in a review in 1941 arguing that at the end of the film, “we realize that the fragments are not governed by any secret unity: the detested Charles Foster Kane is a simulacrum, a chaos of appearances.” Further Borges saw Welles’ film as teaching us that, “no man knows who he is, no man is anyone.” And Borges’ review has been quoted a number of times. The first line in Laura Mulvey’s 1991 book Citizen Kane in the BFI Classics series quotes Borges’ claim that the film is “a labyrinth without a center.” (1.)

These are key elements of the film, I will argue, but they are not in themselves central. In this piece I will show that these elements of Citizen Kane are at times conceived as a “natural” locus around which it is inevitable that all other aspects of the film will be discussed. I suggest that this may have served to cloud matters. Through close textual analysis I present a very different way of reading the film, just as important, that may have been left unrecognised as a result of its being at odds with these consensus perspectives on the film.

————

It is widely known that Orson Welles and co-scriptwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz had some disputes over Citizen Kane’s script, originally written by Mankiewicz with the title “American” but considerably re-worked together. The famous example is of Welles stating that Mankiewicz insisted on showing what “Rosebud” actually was – namingly Kane’s sled – while Welles felt that this was shameful “dollar-book Freud” and would have preferred the word’s meaning to remain unknowable. Many at the time of the film’s release felt that Welles didn’t deserve his co-screenwriter credit and so certainly didn’t deserve to share the Oscar for the Best Original Screenplay. This position was consolidated years later in Pauline Kael’s thoroughly well-composed though somewhat excessive attack upon Welles in her 1971 article for The New Yorker, “Raising Kane.”

It seems to me that the general emphasis on the unknowability of Kane and the anti-objectivity of Citizen Kane may be in part the result of this. Welles’ argument that Mankiewicz made the film overly-rationalist with his Rosebud-MacGuffin may well have had some influence on critics who decided to come out in support of Welles as the film’s “true author” by building up the case for Citizen Kane as his labyrinth. Indeed Mulvey’s book explicitly criticises Kael’s article and specifically Kael’s claim that Mankiewicz deserves sole credit for the screenplay. And although Peter Conrad claims in his Orson Welles: The Stories of His Life (2003) that the film’s “labyrinth does have a centre” Conrad picks up Borges’ metaphor to argue that, “Citizen Kane is wrought with Daedalan cunning, made up of puzzles and riddles. Like a myth it conflates or superimposes different stories. Hearst’s story merges with that of Kubla Khan, from whom Kane borrows the name of his private kingdom; their story is also Welles’.” (152.)

To clarify here, I am not claiming that any of these critics are incorrect in perceiving Citizen Kane to be a mysterious and complex film. Rather I want to propose that this mystery is not the central point of the film. Just as “Rosebud” is not the answer to the puzzle, neither is an abstract, mysterious absence of meaning. Although the idea of telling the story of one person’s life through various different people’s point-of-view was original this is not in itself adequate evidence of the film’s greater complexity than the usual Hollywood fare. In fact this technique only serves to make more apparent than usual a typical Hollywood characteristic. I turn here to David Bordwell in The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985):

Since classical narration communicates what it ‘knows’ by making characters haul the causal chain through the film, it might seem logical to assume that the classical film commonly restricts its knowledge to a single character’s point-of-view. Logical, but wrong. … The overwhelmingly common practice is to use the omnipresence of classical narration to move fluidly from one character to another. (31.)

This characteristic of the average Hollywood movie is all the same made more apparent than usual – and so partially ironised – in Citizen Kane’s direct presentation of its multiple storytellers to the audience through the trope of having journalists interview these characters.

Nevertheless, while there may be tiny hidden contradictions, these multiple narratives in Citizen Kane overall generally reaffirm one another. The notion that Kane cares only about himself, for example, is stated both by Jedediah Leland and Susan Alexander in each of their narratives. Likewise the jumps back and forth through different past time periods and repetitions of these time periods never, to my knowledge, highlight distinct contradictions.

More to the point, and to return to my original argument, even when we are purportedly watching one character’s flashback the visual language does not appear to do a great deal to assert throughout the flashback that this is the case. These scenes often use regular shot/reverse-shot patterns and other elements of the Hollywood continuity system (along with many very innovative visual techniques) that help to maintain Bordwell’s “omnipresence of classical narration.”

————

Initially I perceived this to be a failure of the film to live up to its apparently intended fractured narrative style, but closer analysis of some of these scenes has left me uncertain as to whether I was being too hasty and overly simplistic in this matter. Indeed the first flashback of the film is ambiguous even as to who rightly “owns” it. As Thompson reads from the now-dead Thatcher’s journal we see the scene of Thatcher taking the young Kane from his childhood home. This is certainly Thatcher’s story, but should we assume that the visuals are as much Thompson’s, since he is the one reading and so visualising the scene? Clearly we have here a metaphor for the relationship between writer and director, with the director applying the “vision.” (As well as Welles’ ultimate fantasy, that the writer could turn out the perfect script but be dead so not want to bother with taking any credit: no wonder Welles did so many adaptations!)

As this first flashback progresses there are various signs that suggest that the power in the scene is in the hands of neither Thatcher nor Thompson, but is rather being signed over to the young Kane himself as the owner of the scene (and not only an enormous wealth.) First example: a shot in which the camera appears to be showing Kane in the snow from the outside turns out to be shot from the inside as the camera tracks back to reveal Kane’s mother at the window.

The same track backwards shows Mrs Kane face on (a rare example of a plain face-on image in the film) and follows her fairly long walk through the front room into the kitchen. To me this image can be considered emblematic of Kane’s fantasy image of his mother: it presents both the household as warm in comparison with the snow outside and a vaguely fetishistic steady image of his mother. Kane’s mother is nevertheless visibly moving away from Kane himself, who we continue to see in the background of the shot, suggesting the irreplaceable loss that Kane will always feel. The young Kane being stuck outside this house is surely suggestive both of the older Kane likewise forever outside of his fantasy of his past (seen in the paperweight that he keeps) and of the falsity of this fantasy since even the young Kane was never actually in symbiosis with his mother and the family house.

Second example: this deep-focus image as Kane’s mother and Thatcher discuss Kane’s future places Kane dead in the centre in the background of the image.Third example: a careful composition shot near the end of the scene presents Thatcher telling Kane what a lucky boy he is to be adventuring to the city, while his parents watch on. Very quickly, however, the viewer’s attention is drawn away from Thatcher to young Kane’s intensely angry stare up at Thatcher.

Kane dominates the viewer’s attention just as he will throughout the story. As Kane attacks Thatcher with his sled it appears as if his destruction of this careful composition foreshadows Kane’s future destructive and even self-destructive fate. (Self-destructive since Kane parallels with Welles destroying his own composition here.)Fourth example: As Kane’s mother makes it clear that Kane’s father would like to beat him, Kane re-directs his angry glare towards his father. Everything anti-authoritarian to come from Kane seems to be implied here.

Far from the notion of Kane’s identity as mysteriously absent and primarily refracted through other people’s perspectives in this scene Kane has immense control, even over other people’s flashbacks, just as he takes so much control within the film’s plot. Paradoxically it may even be the case that the script’s technique of purporting to tell the story from multiple points-of-view actually pushes Welles’ film closer than the usual Hollywood movie towards that rarer form that Bordwell notes – of a film restricted primarily to one character’s perspective. Citizen Kane is a film at least as much about power, in terms of form as well as content, as it is about mystery and the absence of objective truth. Without wanting to overstate the case, with this reading a person could argue that the film’s centre sits squarely with Kane himself: as the locus around which power relations play out, not only in the film’s plot but also in its style. I am certain, however, that Citizen Kane is about many things beside this that I haven’t been able to touch on here. I also feel sure that this perspective would benefit from being considered alongside other perspectives on the film.

Ben Dooley.

We could have chosen any year. It could have been 1915, a year that would have allowed us to discuss the evolution of narrative cinema, the rise of a star system, and the war that allowed Hollywood to take over.

Or we could have returned to 1960, the year that European cinema exploded worldwide and past cinema began to be celebrated. It would have given us a good excuse to re-watch L’Avventura, A Bout de Souffle, La Dolce Vita, Psycho and Peeping Tom.

With a joint passion for Classical Hollywood the 1940s seemed appropriate. But even other years may have been more suitable. Indeed, 1940 would have offered up The Grapes of Wrath, His Girl Friday, The Great Dictator and The Philadelphia Story while 1942 would have given us Casablanca, The Magnificent Ambersons, Now Voyager and To Be Or Not To Be. 1946 would have been a particularly rich year with The Best Years of Our Lives, It’s a Wonderful Life and A Matter of Life and Death all in one go.

Yet in 1941 we find ourselves on the cusp of film noir, embroiled in the international outbreak of WWII and shocked by the power of one film that seems to overshadow all others.

We want to use cinema as a time machine, to fill the shoes of a moviegoer between January and December of 1941. We want to see the very images they saw. We want to be plunged into the darkness, feeling our way from film to film.

By focusing on a limited period we are hoping to discover patterns and contradictions between the films of the time, as well as some surprises. In many ways it’s not about the films we know but about the films we don’t and what they can tell us that we haven’t learnt from the canon.

Still we can’t help drawing parallels with the down-and-out movie director Sullivan setting out on his travels, the gangsters driven half-mad in the quest for the ‘Maltese Falcon’ or the shadowy reporters chasing after that elusive ‘Rosebud.’ But perhaps this is as good a place as any to begin our journey…

Christian and Ben.

Recent Comments